Help You Help Future You: Organizing your research projects reproducibly

It's that time of year again – it's time to start a new research project! Planning for the research itself can be daunting, but planning for your work to be fully reproducible is a whole other layer that isn't always emphasized. In this blog post, we'll outline a few project organization principles we teach in our Reproducible Research Practices workshop that we think are really helpful for ensuring reproducibility (among other benefits!).

When we teach this workshop, one concept I like to emphasize is that your computational research should adhere to the same rigor as your wet-lab research does. But often, just by moving our work to a computer, it's easier to let certain research practices slide because, well, it's all in the computer! For example, when you're really in the thick of a project, you might be able to rely on muscle memory for knowing which scripts need to be run and how, and which files they take as input. Let's now fast-forward a bit – you've submitted the paper, and 8 months later, it comes back from review. In the meantime, you've been working on 2 other unrelated projects. Your muscle memory may not be as sharp as it once was. Or it could be worse – maybe you've moved on from your current position, and someone else in your previous lab now has to work with your files, and they never even had the muscle memory to begin with!

These are situations where someone needs to make educated guesses about which files should be used for what purpose. In reproducible science (or really, any science at all), we never want to find ourselves guessing - we want to know. The same concept should apply to computational research: You never want to guess. Consider these additional analogous wet-lab vs computational research scenarios. We probably wouldn't be comfortable with what's on the left, so we shouldn't settle for what's on the right, either.

We'll share a couple of key ways we think about project organization that can help you avoid these pitfalls and improve your project's reproducibility, specifically: organizing your files and organizing your code. And bonus, these guidelines will also help you more easily…

- Write your methods section

- Respond to revisions after you've forgotten about the project for 6-10 months after submission

- Share code and data when the time comes, as per funder and/or journal requirements

- Know your research outputs with confidence, without having to guess

Organize your project files consistently

Having a group-wide, consistent approach to organizing project files will make it easier for you to collaborate on your work, as you'll know what is what. When it comes time to share your data and code, you'll have a much clearer sense of where and what everything is.

To support both reproducibility and collaboration, we recommend establishing version-controlled repositories on GitHub or similar services, such as GitLab, for each scientific project you work on. Then, within this repository, you'll want to adhere to some group-wide standard for file organization. Coming up with a good system can be pretty tricky, so here's one way we approach it (noting that much of it is based on recommendations here!)

In our Reproducible Research Practices workshop, we emphasize project organization with interactive exercises stemming from this baseline GitHub repository: https://github.com/AlexsLemonade/rrp-workshop-exercises. This repository demonstrates an example of how to organize project files, with a clear separation between data, code, and analytical results.

Something you might notice when exploring this repository is that we have quite a few [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] files. These are living project documentation files which should be actively maintained over the course of your research with information such as:

- The role/purpose of each file

- How to prepare/obtain input data for analysis

- How to run analysis code, including setting up the software environment

You can see more examples of how we document analyses in repositories from our OpenScPCA project, where each (mature) analysis contains a [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] with this kind of information (e.g., our neuroblastoma cell type annotation module).

We also recommend taking a bit of time to plan how you will name your files, which is trickier than you might expect! We borrow a lot of the approaches that Jenny Bryan lays out here, and you can see some of this in practice in the repository's [.inline-snippet]analyses/mutation_counts[.inline-snippet] folder. You'll notice that we name our scripts with prefixes like [.inline-snippet]01_[.inline-snippet], [.inline-snippet]02_[.inline-snippet], etc. to cue us in quickly to the order that script should be run in. In this case, we also have a Bash script prefixed [.inline-snippet]00_[.inline-snippet] that runs the other numbered files in order to reproduce the analysis as described in the provided [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] file.

I also want to point out that there are a couple of important files that are not included in this repository, since they are added to participants' repository forks as part of the interactive RRP workshop exercises. These include:

- Dedicated folders for [.inline-snippet]results[.inline-snippet] and [.inline-snippet]plots[.inline-snippet]

- Files associated with package managers that record and handle our code dependencies. We particularly like [.inline-snippet]renv[.inline-snippet] for R and [.inline-snippet]conda[.inline-snippet] (and more recently [.inline-snippet]pixi[.inline-snippet]!) for Python and other command-line tools. Using a package manager will help you maintain your code over time – as software versions change, so do their functions and behaviors. Perfectly good code can sometimes entirely cease to function across different software versions. On top of that, different software versions can sometimes give different scientific results.

Write your code with reproducibility in mind

I confess, this is one of my favorite parts of computational research - it's much easier to re-run an analysis by hitting "Go" and enjoying a coffee while the computer chugs along, than to redo an experiment by running the full protocol again. But, you only get this benefit if you write your code with Future You in mind - don't assume that when you first write the code is the only time you (or someone else!) will run or work with the code.

We often develop our analysis and visualization code interactively, especially when doing exploratory work. Rather than having to dig through your code history to find a record of this exploration, we recommend developing the early stages of your code in notebooks, like R Markdown (or its heir Quarto) or Jupyter. These frameworks emphasize the often experimental nature of code development: You can quickly run small chunks of code, inspect their outputs immediately, and include textual interpretations along the side, and you'll have a full record of the code you ran! Notebooks aren't only for development though - they're a great way to showcase more involved analyses that include both code, plots, and associated text.

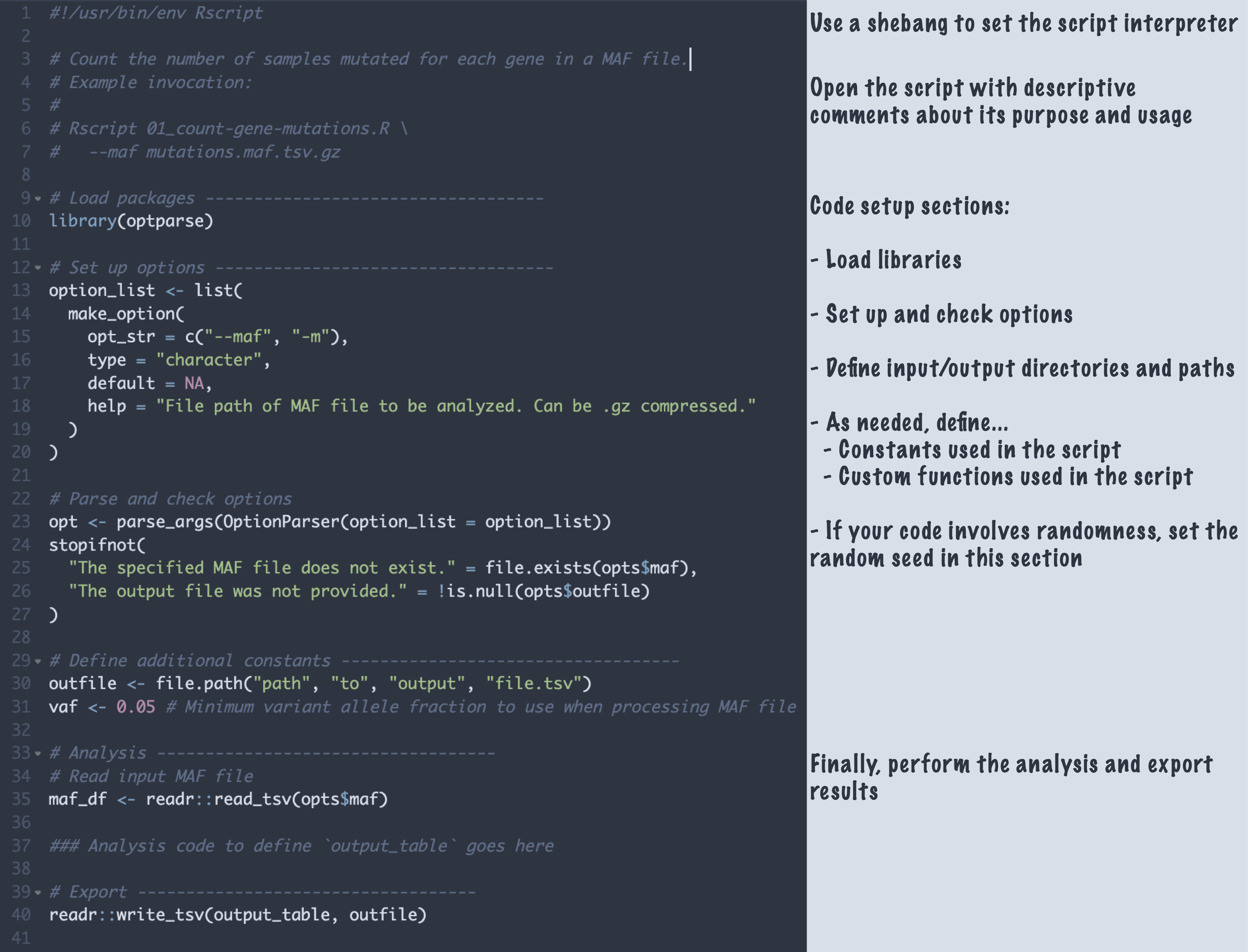

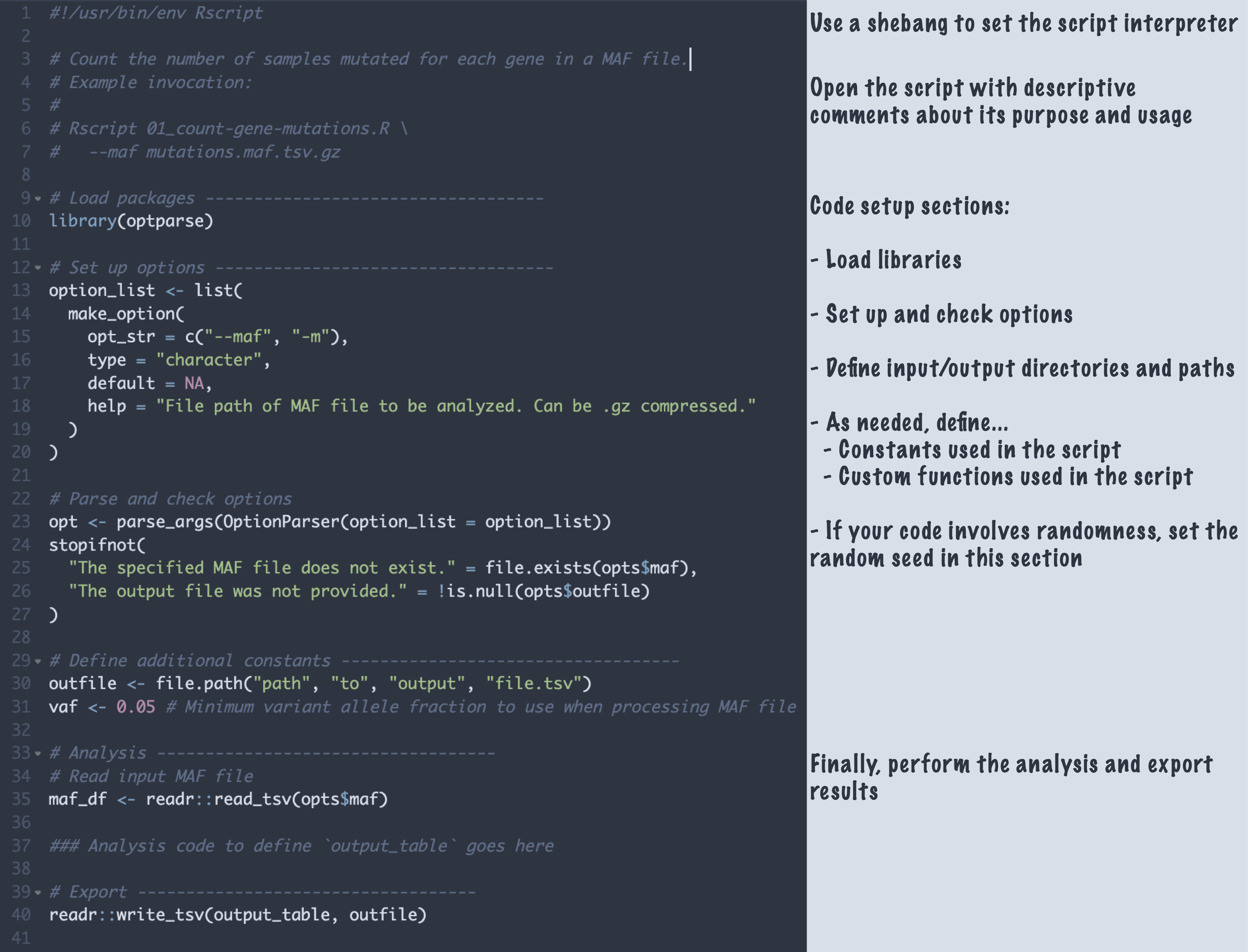

After your interactive development (or in parallel to!), you want to end up with analysis scripts and/or notebooks that can be run top-to-bottom in a fresh environment to fully reproduce your analysis. In the Data Lab, we try to make our lives easier in the long run by writing our scripts/notebooks using a consistent organization. This consistency helps us develop it, helps others review it, and makes it much easier to come back to and update in the future. Below, we show an (abbreviated!) example of how we generally like to structure our scripts.

You can learn more about our thoughts on script and notebook organization from our documentation for the OpenScPCA project, too!

Take the next step toward more reproducible research

More than 50 pediatric cancer researchers have attended our courses on reproducible research practices to learn how to apply these concepts in their work. (Hear from one of them in this blog post!) If you’d like to explore these principles further, check out our curated list of reproducibility resources, and better yet, attend a workshop! Join our mailing list to be notified about future opportunities and take the next step toward making your research more robust, reliable, and reproducible.

It's that time of year again – it's time to start a new research project! Planning for the research itself can be daunting, but planning for your work to be fully reproducible is a whole other layer that isn't always emphasized. In this blog post, we'll outline a few project organization principles we teach in our Reproducible Research Practices workshop that we think are really helpful for ensuring reproducibility (among other benefits!).

When we teach this workshop, one concept I like to emphasize is that your computational research should adhere to the same rigor as your wet-lab research does. But often, just by moving our work to a computer, it's easier to let certain research practices slide because, well, it's all in the computer! For example, when you're really in the thick of a project, you might be able to rely on muscle memory for knowing which scripts need to be run and how, and which files they take as input. Let's now fast-forward a bit – you've submitted the paper, and 8 months later, it comes back from review. In the meantime, you've been working on 2 other unrelated projects. Your muscle memory may not be as sharp as it once was. Or it could be worse – maybe you've moved on from your current position, and someone else in your previous lab now has to work with your files, and they never even had the muscle memory to begin with!

These are situations where someone needs to make educated guesses about which files should be used for what purpose. In reproducible science (or really, any science at all), we never want to find ourselves guessing - we want to know. The same concept should apply to computational research: You never want to guess. Consider these additional analogous wet-lab vs computational research scenarios. We probably wouldn't be comfortable with what's on the left, so we shouldn't settle for what's on the right, either.

We'll share a couple of key ways we think about project organization that can help you avoid these pitfalls and improve your project's reproducibility, specifically: organizing your files and organizing your code. And bonus, these guidelines will also help you more easily…

- Write your methods section

- Respond to revisions after you've forgotten about the project for 6-10 months after submission

- Share code and data when the time comes, as per funder and/or journal requirements

- Know your research outputs with confidence, without having to guess

Organize your project files consistently

Having a group-wide, consistent approach to organizing project files will make it easier for you to collaborate on your work, as you'll know what is what. When it comes time to share your data and code, you'll have a much clearer sense of where and what everything is.

To support both reproducibility and collaboration, we recommend establishing version-controlled repositories on GitHub or similar services, such as GitLab, for each scientific project you work on. Then, within this repository, you'll want to adhere to some group-wide standard for file organization. Coming up with a good system can be pretty tricky, so here's one way we approach it (noting that much of it is based on recommendations here!)

In our Reproducible Research Practices workshop, we emphasize project organization with interactive exercises stemming from this baseline GitHub repository: https://github.com/AlexsLemonade/rrp-workshop-exercises. This repository demonstrates an example of how to organize project files, with a clear separation between data, code, and analytical results.

Something you might notice when exploring this repository is that we have quite a few [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] files. These are living project documentation files which should be actively maintained over the course of your research with information such as:

- The role/purpose of each file

- How to prepare/obtain input data for analysis

- How to run analysis code, including setting up the software environment

You can see more examples of how we document analyses in repositories from our OpenScPCA project, where each (mature) analysis contains a [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] with this kind of information (e.g., our neuroblastoma cell type annotation module).

We also recommend taking a bit of time to plan how you will name your files, which is trickier than you might expect! We borrow a lot of the approaches that Jenny Bryan lays out here, and you can see some of this in practice in the repository's [.inline-snippet]analyses/mutation_counts[.inline-snippet] folder. You'll notice that we name our scripts with prefixes like [.inline-snippet]01_[.inline-snippet], [.inline-snippet]02_[.inline-snippet], etc. to cue us in quickly to the order that script should be run in. In this case, we also have a Bash script prefixed [.inline-snippet]00_[.inline-snippet] that runs the other numbered files in order to reproduce the analysis as described in the provided [.inline-snippet]README.md[.inline-snippet] file.

I also want to point out that there are a couple of important files that are not included in this repository, since they are added to participants' repository forks as part of the interactive RRP workshop exercises. These include:

- Dedicated folders for [.inline-snippet]results[.inline-snippet] and [.inline-snippet]plots[.inline-snippet]

- Files associated with package managers that record and handle our code dependencies. We particularly like [.inline-snippet]renv[.inline-snippet] for R and [.inline-snippet]conda[.inline-snippet] (and more recently [.inline-snippet]pixi[.inline-snippet]!) for Python and other command-line tools. Using a package manager will help you maintain your code over time – as software versions change, so do their functions and behaviors. Perfectly good code can sometimes entirely cease to function across different software versions. On top of that, different software versions can sometimes give different scientific results.

Write your code with reproducibility in mind

I confess, this is one of my favorite parts of computational research - it's much easier to re-run an analysis by hitting "Go" and enjoying a coffee while the computer chugs along, than to redo an experiment by running the full protocol again. But, you only get this benefit if you write your code with Future You in mind - don't assume that when you first write the code is the only time you (or someone else!) will run or work with the code.

We often develop our analysis and visualization code interactively, especially when doing exploratory work. Rather than having to dig through your code history to find a record of this exploration, we recommend developing the early stages of your code in notebooks, like R Markdown (or its heir Quarto) or Jupyter. These frameworks emphasize the often experimental nature of code development: You can quickly run small chunks of code, inspect their outputs immediately, and include textual interpretations along the side, and you'll have a full record of the code you ran! Notebooks aren't only for development though - they're a great way to showcase more involved analyses that include both code, plots, and associated text.

After your interactive development (or in parallel to!), you want to end up with analysis scripts and/or notebooks that can be run top-to-bottom in a fresh environment to fully reproduce your analysis. In the Data Lab, we try to make our lives easier in the long run by writing our scripts/notebooks using a consistent organization. This consistency helps us develop it, helps others review it, and makes it much easier to come back to and update in the future. Below, we show an (abbreviated!) example of how we generally like to structure our scripts.

You can learn more about our thoughts on script and notebook organization from our documentation for the OpenScPCA project, too!

Take the next step toward more reproducible research

More than 50 pediatric cancer researchers have attended our courses on reproducible research practices to learn how to apply these concepts in their work. (Hear from one of them in this blog post!) If you’d like to explore these principles further, check out our curated list of reproducibility resources, and better yet, attend a workshop! Join our mailing list to be notified about future opportunities and take the next step toward making your research more robust, reliable, and reproducible.